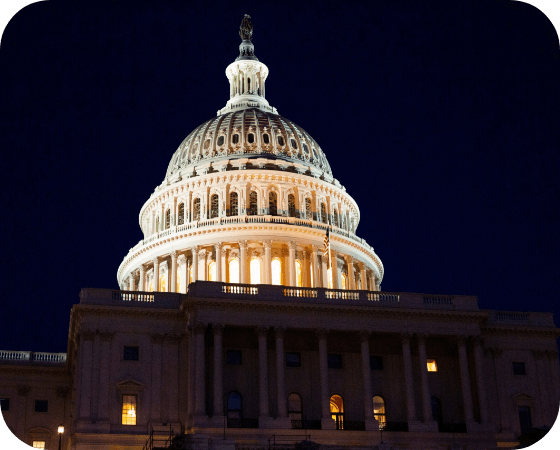

Hill staffers say they’ve had enough. Long hours, low pay, and cases of emotional and physical abuse are driving more and more congressional staffers to form the Congressional Workers Union with the hope of delivering better working conditions and higher pay. But forming a union on the Hill is easier said than done, and staffers hoping for better working conditions in their current roles might have to wait for some time.

Why unionize? The cost of living in the Washington, DC area is notoriously high, with the average rent for a studio apartment in the District going for $1,891. Finding the money to cover high rent can be hard – 13% of Washington-based staff (about 1,200) make less than $42,610 each, which is the average salary needed to cover basic essentials like rent and groceries in DC. On top of that, staffers face sub-par working conditions that have been regularly documented in the Instagram account @dear_white_staffers, which details stories anonymously of poor treatment by members and staff, harassment, burnout, and more. Given all these pain points, it’s no surprise that turnover among House staff is at its highest level in 20 years.

High turnover among Hill staffers has negative implications outside of Congress. For one, it’s bad news for advocates because it gives them fewer opportunities to develop meaningful relationships that help them advance their cause. Additionally, an ever-changing staff makeup deprives Congress of the institutional knowledge and policy expertise it needs to pass legislation that impacts the American people. By boosting pay and improving working conditions, congressional staff might be compelled to stick around the Hill longer – allowing them to forge deeper bonds with advocates, and more strongly familiarize themselves on the issues important to them and develop legislation that works better for most Americans.

Unfortunately for staffers, there are a lot of challenges to forming a union on the Hill. These include:

- Legal issues. Congress is exempt from federal labor laws that protect most US employees’ labor-organizing activities. Absent any legal protections, staff are reluctant to publicly push for a union because it could lead to them being fired or blacklisted.

- Partisan problems. In general, Democrats have supported staff efforts to unionize, while Republicans do not. During a March 2 congressional hearing on a bill to allow staff to collectively bargain, GOP members said unionization efforts were “impractical,” would add to “even more dysfunction in Washington,” and amounted to a “solution in search of a problem.” Outside of the hearing, Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) has referred to unionization as a “terrible idea,” and Sen. Mitt Romney (R-UT) said giving staff the ability to organize is “nuts.” But it’s not just Republicans who stand in the way – Democrats who are generally pro-worker and pro-union could be at risk for allegations of hypocrisy if they fail to support their own staff’s organizing efforts.

- Operational considerations. Congressional offices aren’t like normal businesses that can raise salaries and boost benefits based on market conditions. Instead, each office is provided a yearly allowance that covers a range of expenses, like staff pay, travel funds, and mail. Unfortunately, these allowances don’t provide much flexibility on staffers’ salaries. While the Fiscal Year (FY) 2022 omnibus appropriations bill did boost the yearly allowance for House offices by 21%, this doesn’t guarantee House staffers will see higher pay as a result. More so, each congressional offices operates independently, which means a unionized congressional staff would essentially involve hundreds of individual unions throughout the Hill. Additionally, there’s a chance majority and minority staffers on each committee could try to organize separately, adding to the number of potential unions.

What’s next? Rep. Andy Levin (D-MI) introduced a resolution that would remove the exemption barring staffers working for individual members, committees and leadership offices to form a union. To date, Levin’s resolution has garnered 165 cosponsors, all Democrats. While this resolution would only apply to the House, Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) has signaled interested in introducing a resolution for the Senate side.

Beyond this, next steps are unclear. Levin’s resolution will require approval from both the House Committee on Administration and House Committee on Education and Labor, and even then, the measure needs the support of 61 additional Democrats before it can secure the 217 votes needed to pass the House. On top of this, the resolution has some technical issues that will take a few weeks to address. And while Levin’s resolution would face at least attainable odds of passing in the Democratically controlled House, any Senate resolution on collective bargaining would have little chance of garnering the 60 votes needed to override a filibuster. No Republican senators have endorsed efforts to unionize, and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) has voiced some skepticism about staffers forming unions.

However, Hill staffers are undeterred in their efforts to advocate for the ability to form unions. As long as low pay and poor working conditions continue to be a fact of life for employees of congressional offices, staffers will continue to voice for changes to allow them to organize – even if the realization of those changes may be a long way off.