E&C Leaders Release FDA User Fee Package

On Wednesday, bipartisan leaders of the House Energy and Commerce Committee released a legislative proposal to reauthorize the Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) ability to collect fees from drug, biosimilar, and device manufacturers for five years. Additionally, the bill contains several policy riders that would give the FDA more control over the accelerated approval program, promote diversity in clinical trials, and reinstate a ban on electric shock devices for aggressive behavior, among other items. The Health Subcommittee is expected to markup the user fee bill next Wednesday, with the goal passing the legislation in Congress by August.

FDA Approves Marketing of New Alzheimer’s Test

The FDA on Wednesday approved the marketing of an in vitro diagnostic test for early detection of amyloid plaques associated with Alzheimer’s disease. Produced by Fujirebio Diagnostics, the test works by measuring the ratio of certain proteins in the fluid that surrounds the brain. In a press release, the FDA said the availability of an in vitro diagnostic test could eliminate the needs for PET scans, which are time-consuming and expensive. In a clinical study, the test detected Alzheimer’s disease in 97% of people who had amyloid plaques present in a PET scan. The National Institute of Health (NIH) estimates that over six million Americans may have Alzheimer’s disease.

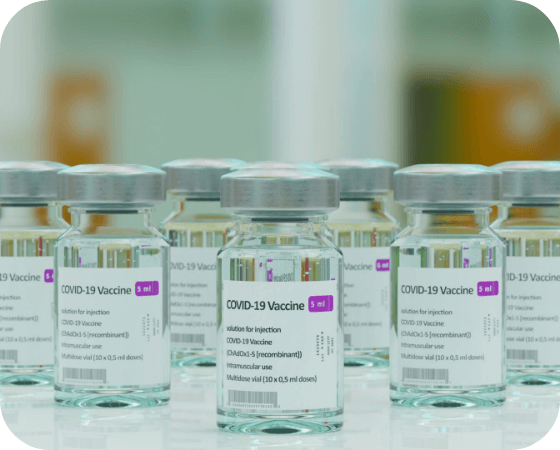

Survey: Most Parents Will Wait to Get Young Kids Vaccinated

18% of parents of children under 5 say they’ll get their kids vaccinated for COVID-19 as soon as a shot is authorized, according to a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation. Another 38% say they’ll take a “wait and see” approach before getting their kids vaccinated, while 56% want more information about vaccine safety and efficacy before making a decision. Delays in FDA authorization of vaccines for young kids also left parents with mix feelings, with 22% saying the delays have made them more confident in the vaccine and 13% sayings the delays have made them less confident. The survey was conducted in mid-April 2022, right before Moderna filed to authorize its vaccine for kids under 5 with the FDA.

Rent-A-Cops Arrive on Capitol Hill to Provide Security

To help address staffing shortages, the US Capitol Police (USCP) recently started deploying private security guards around the US Capitol Complex. The private officers will wear grey dress pants and a navy-blue blazer rather than the police uniform and will be unarmed. According to the USCP, the private officers will be stationed inside secure building like the House and Senate office buildings and will help augment existing patrols.

ICYMI: Jazz in the Garden Returns to National Mall on May 20

In two weeks, Jazz in the Garden will return to the National Gallery of Art Sculpture Garden along the National Mall. The free concert series is a favorite summer tradition in Washington, DC, and this year’s series is set to features several genres including jazz, Afro-Brazilian, and bluegrass. The series was closed during summer 2020 and was only open on a limited basis for summer 2021. Guests will be required to register for the concert in advance.